Authors, Laura Chamberlain, Consultant, and Vinod Jose, Principal, at Amane Advisors.

In the U.S., water service lines made of lead and galvanized pipe are putting millions at risk of lead exposure. Lead-laden pipes can corrode and leach the contaminant into tap water, especially when water has high acidity or low mineral content. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates today there are at least 6 to over 10 million lead service lines (LSLs). Supporting local water utilities to identify and replace these LSLs with lead-free pipe is the most certain way to reduce the risk of lead exposure.

Yet common challenges around finding and replacing LSLs have stymied local efforts. Municipalities may have inadequate or unsystematic records and techniques to locate and identify buried LSLs with high certainty. This makes it all the more difficult for water utilities to build an inventory of service lines that can be used as a basis for replacement programs. Another issue is inadequate funding. These challenges may be complicated further considering most replacements are likely located within the portion of LSLs on private property. Replacing private LSLs may raise tough questions around financial responsibility between a property owner and a utility, appropriate funding sources, and right-to-entry.

A utility’s wholesale lead service line replacement (LSLR) program may take several years to complete. Common steps may entail: early engagement with stakeholders such as homeowners and schools, service line inventory, pitcher filter delivery, full LSL replacement, and follow-up testing. A successful program also includes ongoing procedures and activities: annual compliance report submissions to a regulator, sample site monitoring at schools and homes, and risk communication with the public about LSLs. Funding of course buoys a LSLR program, and a utility is generally responsible for securing those funds from state and federal government.

“The Flint, Michigan crisis in 2014 heightened public concern about the possibility and consequences of lead in tap water and has increased pressure on utilities and government to take long-overdue action.”

Yet the persisting regulatory and economic barriers need to be addressed to accelerate action. The good news is that both public and private sectors have stepped up by offering solutions and tools to support LSLR programs.

Federal regulations for lead in drinking water

Today there is a “lead ban” on pipes per the U.S. Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986. The national Lead and Copper Rule was introduced in 1991 to regulate and mitigate lead in drinking water. Regulating lead levels is based on using a treatment technique to control water corrosivity. This could be done by adding orthophosphate to coat pipes in the water distribution system. Lead mitigation is based on the EPA’s action level at 15 parts per billion (ppb) using a 90th percentile calculation. This calculation means that if more than 10% of tap water samples measure lead at or above 15 ppb, a utility exceeds the action level and is subject to taking certain actions to mitigate lead in the water system. Actions a water utility can take include water quality parameter monitoring, corrosion control treatment, source water monitoring/treatment, public notification and education, and LSLR.

The reality of the issue

Replacing the estimated 6 to 10 million LSLs comes with a huge price tag. A 2016 study conducted by the American Water Works Association estimates average full LSL replacement costs at $6,106 per lead service line. This means fully replacing the nation’s LSLs could cost over $61 billion.

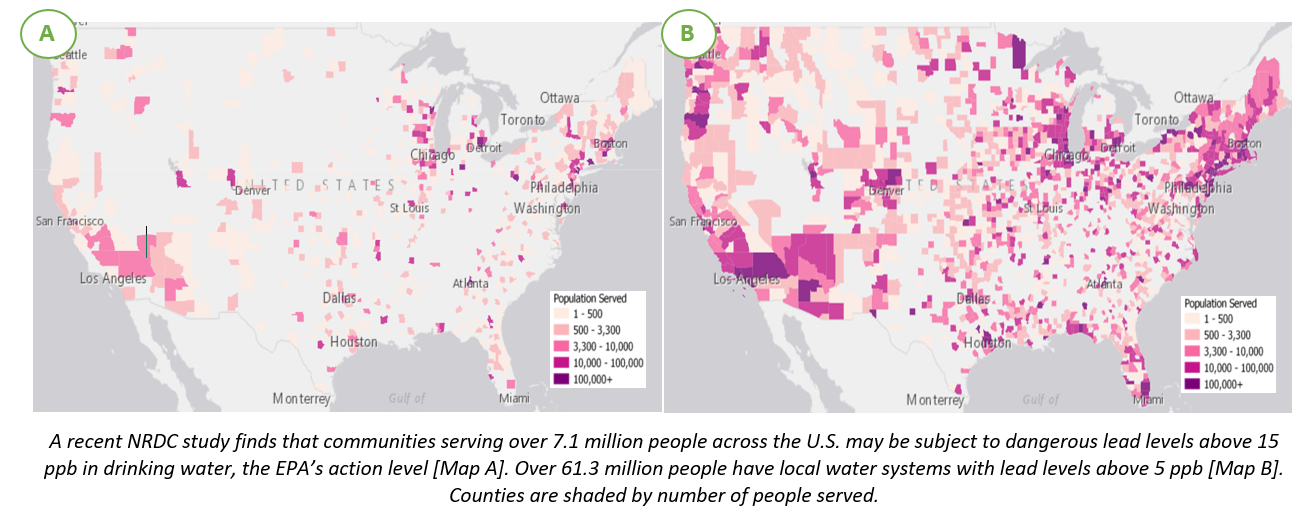

The scale of lead presently in tap water also underscores the urgency to address the issue. In 2021, the advocacy group Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC) evaluated violations of the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule between January 2018 and December 2020. The study used data from the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Information System to determine that nearly 2,000 drinking water systems serving over a combined 7.1 million people reported 90th percentile lead samples above 15 ppb – the EPA action level. The NRDC confirms nearly 5,000 public water systems serving over a total of 61.3 million people, or over 18% of the U.S. population (source: US Census, on December 31, 2020), had 90th percentile lead samples above 5 ppb. It is likely that the EPA data do not cover the full extent of lead in drinking water, nor do the data mean that all members of an affected water system are exposed to the contaminant in drinking water. Nonetheless, the data clearly indicates the pervasiveness of the issue with exceedances found in urban and rural areas.

The staggering figures also underscore the risk of lead exposure, especially in the most vulnerable populations. These most at-risk groups are pregnant women, infants, and children under the age of 6, according to the U.S. CDC. The CDC states there is no safe level of lead for young children. Even low levels of lead exposure to young children can result in serious long-term health effects including lower IQ and learning and behavioural problems from impaired brain development and nervous systems. In adults, prolonged lead exposure can lead to stillbirths, kidney damage, and elevated blood pressure.

Regulatory landscape

The need to get the lead out continues to be unmet despite historical efforts around regulating lead in water and updating national regulation has been long overdue.

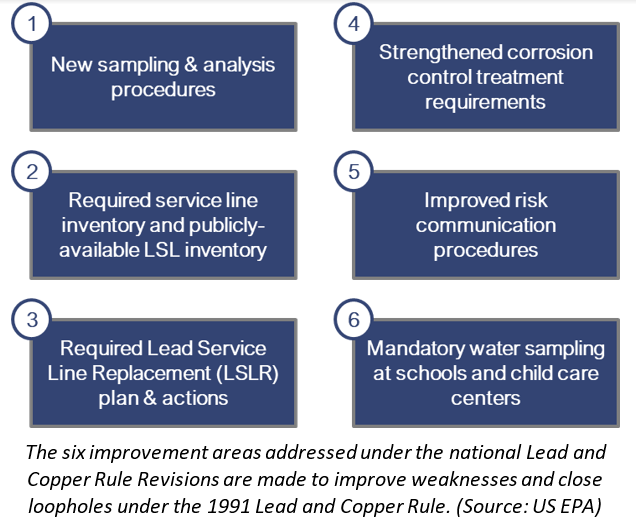

After 30 years since the original Lead and Copper Rule was introduced, on January 15, 2021, the EPA announced several new provisions and changes under the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions. These Revisions will go into effect on December 16, 2021, to strengthen the original Lead and Copper Rule. The Revisions can be broken down into six components (see image). Each component introduces key specific changes that utilities must be aware of. For instance, under new sampling and analysis procedures is a new requirement to collect a 5th-liter water sample to test for lead instead of just a 1st litre sample from homes with known LSLs.

Critically, the Revisions maintain the 15-ppb action level but also define a trigger level at 10 ppb. The trigger level means that water samples with lead levels at or above 10 ppb but at or below 15 ppb may require utilities to perform public outreach and kickstart LSLR. A goal for the annual LSLR rate will be determined in agreement with the utility’s state. Based on the aforementioned NRDC study, thousands of water utilities exceed the trigger level and thus will have to deliver mandatory LSLR. Also, partial LSLR will no longer be an acceptable practice under the new Revisions meaning both the public and private side of an LSL will need to be replaced.

October 2024 is the expected compliance deadline for water suppliers to complete two major activities – conducting an initial service line inventory and developing a LSLR plan. Utilities will be required to deliver publicly available inventories for systems with lead or galvanized service lines, and/or “unknowns” meaning service lines made of undefined material. A LSLR plan will account for funding strategies, replacement procedures on both the public and private side of LSLs, and strategies handling “unknowns”.

These are costly and time-sensitive deadlines for many water utilities responsible for generating funds to support water infrastructure programs like LSLR. The good news is that there is a major federal infrastructure bill under consideration promising to infuse more money into the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund for LSLR. As of August 2021, the INVEST in America Act (H. R. 3684) would introduce $15 billion toward LSLR, with priority assistance given to disadvantaged communities and low-income homeowners. The bill also outlines a $10 million Lead Inventorying Utilization Grant Pilot Program to support municipalities with at least 30% services lines known or suspected to contain lead. Future government spending is a much needed and welcomed step to help close funding gaps for utilities tasked with overseeing these LSLR programs.

“The American Jobs Plan will put plumbers and pipefitters to work, replacing 100 percent of the nation’s lead pipes and service lines so every American, every child can turn on a faucet or a fountain and drink clean water.” – President Joe Biden

Pushing the status quo

Public officials and utilities will have to juggle several procedures and activities to meet the ambitious deadlines under the new Revisions. It is possible that certain utilities must follow more stringent state or local laws as well. To achieve the deadlines and the many expectations set by the EPA and state agencies, there needs to be more guidance and solutions to support utilities in accelerating LSLR.

A number of actions could promise more opportunity for utilities to achieve equitable, successful LSLR programs.

- LCRR Master Plan: Above all, water utilities must first delineate the steps and time needed to meet the 2024 deadlines for a LSLR plan and service line inventory. Having a publicly available Lead and Copper Rule Revision or LCRR Master Plan encompassing all lead-management programs is critical to serve as a bedrock for transparency and consensus-building. Moreover, a utility can use the LCRR Master Plan to identify and prioritize programs needing the most time and funding to complete. Specifically, the LCRR Master Plan should include a broad vision, as well as priorities, procedures, and metrics tracking results of all six components of the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions.

- Along with formulating the Master Plan, utilities should begin to collect and digitize relevant records pinpointing pipe location and indicating material type. This serves as a necessary preliminary step to build a service line inventory. Gleaning existing information such as tax records, water service/tap cards, local plumbing codes, and construction records may indicate regions within a given area where there is a higher likelihood of existing lead pipes.

- More dedicated funding: Local authorities and public water utilities overseeing the delivery of water infrastructure improvements are often cash-strapped yet are responsible for funding lead management projects. The Master Plan is a steppingstone for municipalities to budget all lead management activities and consider funding sources to meet the budget demands. Sources of funding traditionally come from water tariffs and local, state, and federal government.

- Lobbying local, state, or federal government and environmental bodies to increase financial availability is one possibility for municipalities to receive reliable funding streams.

- The aforementioned INVEST in America Act offers even more promise to connect federal dollars to local lead management programs. During a speech in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, President Biden acknowledged that investments “too often … have failed to meet the needs of marginalized communities left behind.” The bill prioritizes funding to reach the most in-need communities including communities of colour and Tribal communities. This proposed funding, however, would likely only apply to LSLR and not fund service line inventory, and leaves a $46 million funding gap for full LSLR.

- Being equitable and inclusive: According to the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions, all lead piping must be fully excavated from service lines, including on the private side. Per local regulations, many municipalities can replace private LSLs, but are prohibited from using public funds to pay for it leaving the property owner financially liable. The LSLR Collaborative states that offering financial assistance and loan programs to private owners may be one option to relieve financial burden. This is especially important to achieve an equitable LSLR program benefiting all residents. Water utilities can establish partnerships with local foundations, NGOs, and key elected officials to further engage the community and homeowners about full LSLR, how it impacts them, and funding resources.

- On solving inventory: More software solutions have come to the market to support a utility’s service line inventory as a critical step before initiating a full-blown LSLR program. Significant uncertainties around LSLs including location and material type of the pipe are commonplace. Utilities can gain more confidence with their inventories by using machine learning from software companies. Software using digitized records mentioned under Step 1 can improve certainty in inventory and save money for a utility.

- Solutions beyond inventory: Water utilities can also use software solutions to meet regulatory compliance handling sampling sites, from delivering kits and water pitchers to data management. Collecting both 1st and 5th litre water samples to test for lead is important but also more resource demanding for utilities. Private companies have developed at-home water quality testing kits for residents to test for lead at the tap and support utility and facility water sampling programs. Especially for utilities dealing with sampling countless private and public taps from homes to schools, some private sector players offer digital platforms to help utilities manage sampling kits between the resident and labs. Private companies are available to support utilities sending and delivering pitcher filters to homeowners with lead exceedance levels and wherever LSLR occurs. A single digital platform can serve as a utility’s clearinghouse to collect and share information and data internally, with the community and regulators.

Pushing forward

Removing lead from water infrastructure is a huge feat that will require heavy lifting from utilities to engage stakeholders, replace LSLRs, and manage data. To achieve the tasks required to stay in compliance with the forthcoming LCRR, utilities need more funding streams available to eliminate LSLs on both the private and public sides. Utilities can also seek software solutions to streamline the complex data management and multiple workstreams to achieve a more cost-effective and equitable replacement program. It is promising to have the federal government pledge to fund LSLR, but using these funds to take the necessary, tangible steps is what truly matters to protect public health.

Do you have an article to share? Click here to submit or if you’d like to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, click here.